This post is a part of the 2017 CQuIC computing summer workshop tutorial materials.

A lifecycle model of productivity

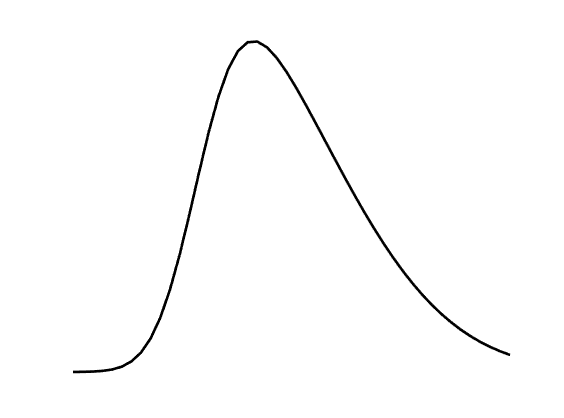

As having been often observed, when we work on a subject, we usually experience the following productivity curve over time as plotted in the figure below.

The curve is the lifecycle on how working on the subject yields valuable outputs, which typically includes a slow and low-efficient starting phase, a rapid climbing phase, a flat peaking phase and a slow decaying phase. In fact, this not only can be seen in task productivity but also occurs on almost everything in our daily lives, like people’s activity level over days and ages, the profit level a fashion or a product follows, the population growth curve of species in a resources-limited environment and so on.

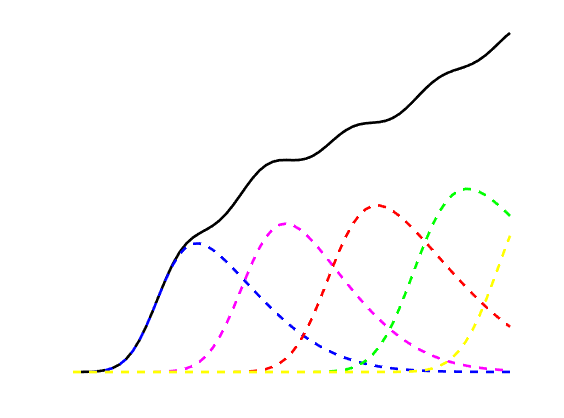

Now, imagine you have a bunch of subjects to work on over time and each of them has a similar lifecycle curve. You can arrange when you start to work on your subjects, and your peak productivity level working on the next subject might grow a little bit higher than the previous one.

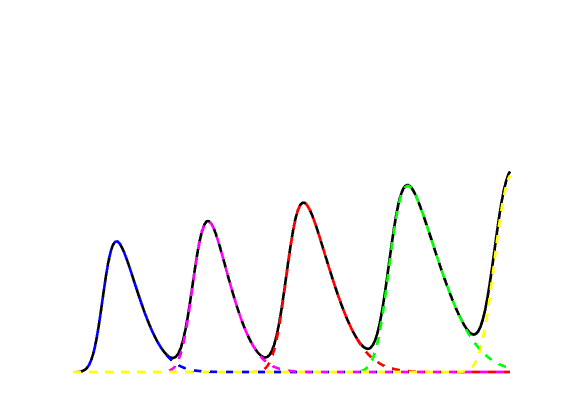

We consider two scenarios. First, as shown in the figure on the left below, we continue working on new subjects before the previous subject’s productivity level decays.

|

|

Obviously, the overall productivity curve experiences a non-decreasing growth over time as individual tasks’ productivity curves overlap.

Next, we consider increasing the intervals between tasks so that the overlap between tasks is small. We could find the productivity curve illustrated in Fig 2 (B) above.

Here are some conclusions based on the comparison of the two cases:

- The overall productivity level can be maximized if different task cycles overlap.

- The condition to have non-decreasing overall productivity growth is that the joining cycle’s productivity curve starts increasing steeper than the decaying slop of the cycle started before it. In other words, it would be ideal to start a new task cycle earlier before the previous task cycle peaks.

- As you can imagine, the total long-term productivity curve will follow the growth rate of the peak productivities of the sequential task cycles which is determined by the improvements of using more efficient tools, mastering common skills and the ability of bundling many tasks together. Therefore, to keep up the positive growth of productivity curve in the long run will require us to keep learning from the past and mastering more tools and skills, as well as to automate and bunch more and more tasks at once.

Although I am using a simple skewed normal distribution to represent the typical productivity cycle curves, it should be easily adapted to real cases of competing dynamic processes when the resources are limited, and the conclusions above should still hold.

Create a sustainable system for continuous growth and convergence

What does this implies to our research projects?

- If you feel you are going to reach the climax of your current research project, it could also be a good time to wrap up and start thinking of your next project.

- Build your path on top of what you are good at and reuse your skills and knowledge gained in the past. This is usually most successful people do.

- Keep reading and discussing new ideas which have some overlap with your current research but not exactly the same. This might help you open up a new future path.

- Have a list of projects/subjects/skills ordered in terms of maturity (such as in alpha, beta and mature phases). Set up corresponding goals and strategies for each set.

- Take some time to learn new tools and automate some common tasks when you get a chance, which might pave the way for you to be more productive.

- Think and reflect on your past experiences periodically. You may “walk” slowly, but try not “walk” backwards.

- Study some fundamental theories from time to time which you think can be used in your future studies (like the summer studies we have been doing).

- Have a big picture and roadmap in your mind and make things coherent as a system. If you are not that visionary, listen to the advice from the elders and friends and build your exploration map on the shoulder of giants. This could help you achieve long-term goals step by step, and coordinate your plans.

Generalize to multiple dimensions and other cases

Obviously, you can easily generalize the task cycles to things related to collaborations, knowledge growth and tool using. In terms of improving productivity and efficiency, similar conclusions could hold. The key is to create some overlaps and continuous growth.

What does this model implies for using version control tools and programming?

- Work on different branches and features at the same time. After finishing up testing each of them, merge them together to the main stream.

- Divide a big program into smaller modules and write small functions which can be relatively easily tested and combined with different other modules to achieve various goals.

- Separate your functions on computing, data manipulation and plotting so that they can be reused in different cases and you don’t need to reproduce your data every time you want to plot out the results.

What is said about collaborations?

- Have some overlaps of interests yet still some variances of view points with collaborators. This will help the healthy growth of collaboration relationships and productivity. Same is true for other relationships of pursuing outcomes while reducing entropy to be stable.

- Starting from one easy collaboration before jumping into more complicated ones. Give some priority for collaborative works based on how ready they are going to fruit.

- Don’t just focus on one thing, but also have some branching-outs and divergent discussions with your collaborators for possible future works whenever conversions are not as productive.

- When you get a desk in an office, use the opportunity to talk to people in the same office–whether related to your research or not, things will grow.

- Work in parallel with collaborators on various things and prioritize tasks to break down barriers towards progress. For many cases, it is important to learn and maybe develop some shared tools for better workflows.

- Sharing and developing program and documentation libraries inside and outside of a research group. Maybe every member can only contribute a little when they are working on their projects, but, overtime, these unique libraries could become a great advantage to help new group members to quickly take off on their researches and to improve the group’s work efficiency.

- Have some collaborative open-source/open-science projects and organize some public events, if possible, to help the group reach out to fresh minds. This is usually how the ecosystem and opportunities grow for your own research and the community’s well-beings.

- In a large scale, how the ecosystem grows will eventually determine how fast and healthy the group and society evolves. Never settle. Continue seeking for new possibilities.

A systematic open-science framework

As a community, knowledge can be shared and discoveries can be achieved together in a relatively efficient fashion if less barriers but more shared common goals. Freedom can be maximized by fundamentally increasing the energy level as well as decreasing the entropy level. Optimization should be pursued in a global view rather than local. Without positive interactions, things can hardly be done as a whole. Yet, a well organized division of workloads, priority of doing things and the ease of open-access to common tools and knowledge will help the community form a sustainable ecosystem for long-term continuous development of discoveries, humanity and civilization.

In the sense of organizing collaborations, version control technique is a science to be discovered even more in-depth than ever before and a practice to be sharpened to be even better by being examined in our real life. Even though individuals can definitely work things out on their own, it is better to have people organized and coordinated as a whole for a sustainable continuous development. Without systematical cooperation in a large scale, conflicts, ignorance and duplications could waste our energy and bring in painful experiences for people and slow down the development of the community in the end.

Don’t forget what do you live and work for.

Some helpful version control publications and resources

- Good Enough Practices in Scientific Computing.

- Open science framework.

- Github and Zenodo integration for citable work.

- Elsevier and Mendeley Data repositories.